"In the mountains, all is pure, all is calm; all complication is cut off. Rare are they who know to listen; happy they who possess wisdom. If the cold wind stings and bothers you, sit in the sun; it is always warm there, its hot rays burn like flames, while opposite in the shade, all is frost and snow. One pauses on ledges, one climbs to the foot of high clouds, one sits in the depths of a gorge, one passes windy grottos. Here is the realm of harmony and joy, where the past and the present become eternal."

-- Buddhist Poem, China, 500AD

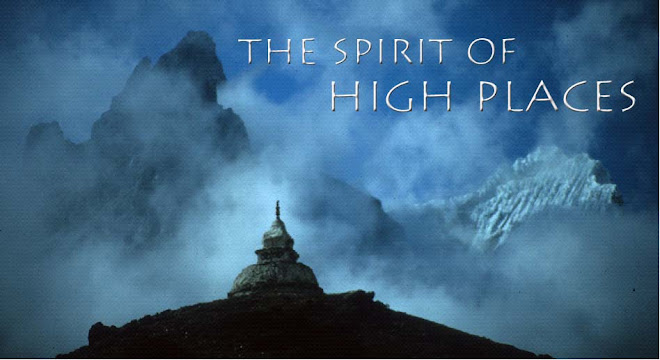

Throughout the ages people have looked to the mountains as the very embodiment of life's spiritual quest. It is here that the landscape of the mortal reaches closest to the heavens. We find in the heights a grand stage for life's divine play.

Mirce Eliade writes, "the symbol and religious significance of mountains is endless,” and any perusal of the great myths and epics of history shows us the breath of which the mountain symbol has entered our thinking. The most common view of the mountain is as the axis of the spheres. It is on Dante's Mt. Purgatory where heaven meets hell. In the Odyssey, Homer describes the summit of Olympus as a divine realm of light and bliss. Confucius praised the mountains as symbols of the stability needed for a proper life. In the Analects, he writes, "the wise take pleasure in water, the benevolent in mountains."

In China, the phrase "to enter the mountain," means to embark on a spiritual or religious quest. The isolation and simplicity of mountain landscapes offers the opportunity to strip down the self, to stowaway all but the raw essentials, opening what the Zen masters call the "original face."

True self-knowledge is the aim of the mystic. The goal of this knowledge is to reconcile our own lives with the larger tale of existence. Joseph Cambell writes, "the purpose of all myth and ritual is to bring one's individual life into accord with the universal."

Mountains are such potent symbols in this struggle due to the effects they have on our consciousness. To enter the mountain world is to return to a landscape of primordial simplicity. Here is sky, and earth, and cloud, and sun: a basic expression of the dynamic nature of earth.

The Dali Lama teaches that the greatest wisdom comes from meditating on emptiness. But in a world of such unprecedented diversions, with lights and sounds and social symbols, emptiness is the furthest state of the modern mind. We are inundated by information to fill in any void. The calm mind of the mystic is in short reserve.

But not in the heights.

In the Snow Leopard, Peter Mathesen writes, "the emptiness and silence of snow mountains quickly brings about those states of consciousness that occur in the mind-emptying of meditation."

Mountains could be referred to in psychological terms as innate releasing mechanisms. These are forms within the physical world capable of opening a view into our subconscious. Carl Jung's extensive research into the human mind describes the outer world as a landscape of primordial symbols. When we encounter one, a memory is released from our subconscious mind.

Jung writes, "Thinking in primordial images -- in symbols that are older than historic man, which have been ingrained in him from earliest times, and eternally living, outlasting all generations, still make up the ground work of the human psyche. It is possible to live the fullest life only when we are in harmony with these symbols. Wisdom is a return to them."

Mountains release these forces of the psyche. We can find in them a symbol for the darkness of our shadow self, the uncontrolled nature of the world, the sublime, the quiet of the spirit, and the suffering of our physical form.

It is said that any journey into the world is a journey to the self. By experiencing our lives in different contexts, we open more fully the knowledge and wisdom we store inside. Our lives in the physical world sculpt out the contour of an internal geography. The extent of which we explore this geography opens to us our "original face."

With this we pass beyond the plane of reasoning and language. The Athabaskans of Alaska have a tradition of not talking about the greatness of a mountain. A child doing so would be told, "do not speak, your mouth is small."

So we are left with symbols. To walk across timberline is to return to a land of primordial simplicity; to touch an age in human history living quietly within you, waiting for an experience to feed it life.

There is an old Gaelic mantra:

Let our spirits be mountains,

Let our souls be stars,

Let our hearts be worlds...